207 SQUADRON ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORY

WORLD WAR I

1917 HP O/400s

During May and June 1917, the Squadron received eight

more Handley Pages from England to replace the Short bombers.

The Squadron strength now stood at 18 aircraft, 10 in one

flight and 8 in the other. The new aircraft were O/400s, a

development of the old O/100s.

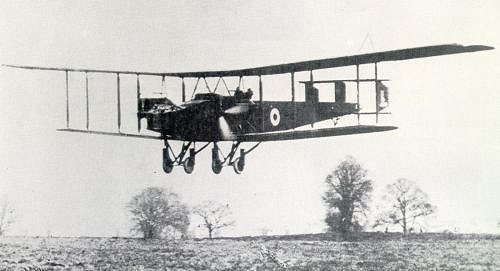

Handley Page O/400 bomber D8345 of No.7 RNAS about to land

As one of the first "all Handley-Page

squadrons", No.7 was something of a showpiece and was

frequently inspected by officers of the Allied High Command.

Early in June, the Squadron was honoured by a visit from the

King and Queen of Belgium, both of whom flew in Squadron

aircraft. Their pilot was Squadron Commander J T Babington

DSO, a new arrival on the Squadron, who was to take command

from Squadron Commander Allsop at the end of the month. (Sqn

Cdr John Babington, had been CO of RNAS Manston and was in

charge of the Handley Page Training Flight (also known as the

'Handley Page Squadron') which by the end of 1916 had been

set up at Manston to receive and prepare ex-factory HP 0/100s

for France and to train their aircrew).

In July 1917, the establishment of Handley Page squadrons

was reduced to 10 aircraft and to meet this change, the

flight of 8 aircraft was removed to the other side of the

airfield to form No.7A Squadron. It continued, however, to be

controlled by No.7 Squadron until December 1917, when it was

renumbered No.14 Squadron RNAS (later No.214 Squadron RAF)

and became an independent unit.

On 31 July 1917, the Battle of Ypres commenced and from

then until mid-November, when the battle ended, the Allies

waged a vigorous and unremitting air offensive in support of

the Army. The RNAS squadrons, including Nos.7 and 7a, kept up

constant day and night attacks on enemy airfields and coastal

targets. They also bombed railway stations, junctions and

depots in an attempt to isolate the battlefield. This was one

of the earliest examples of the use of aircraft in the

interdiction role. On the night of 16 August, Nos.7 and 7a

Squadrons made their most successful night attack. In support

of the British Army's attack at Lanemarck, they raided the

Thourout railway junction and ammunition dumps with 14

aircraft, all of which found and bombed the target. Nine tons

of bombs were dropped, ranging from 65 to 250 pounds.

Explosions were still taking place 90 minutes after the last

aircraft left the target area and the fires were visible from

behind the British trenches.

During this autumn of 1917, the Flanders RNAS Command

reached the peak of its bombing power. Attacks such as the

one on Thourout became commonplace and the tonnage of bombs

increased to an average of 6 tons per raid during September.

Between the nights of 2 and 4 September, Nos. 7 and 7a

Squadrons dropped over 16 tons of bombs on the Bruges docks

alone. The amount of destruction achieved by these raids is

perhaps best shown by the importance attached by the German

High Command to the elimination of the Dunkirk Command.

From September, the towns and airfields of the Dunkirk

Command were subjected to nightly attacks from land, sea and

air. So intense were these attacks that the RNAS Aircraft

Depot was forced to decentralise into a series of sub-depots

and parks. Severe though these raids were, they completely

failed in their main aim of curtailing Allied bombing. Not

only did Allied bombing increase but the scope of targets was

widened.

A good example of this fortitude was the attempted attack

on Cologne by a single aircraft of No.7 Squadron on 20

October 1917. Piloted by Flight Sub-Lieutenant R G G Gardner,

this aircraft encountered extremely bad weather about halfway

to the target and was forced down to 2,500 feet. At Duren,

some 20 miles from Cologne, the aircraft was down to 2,000

feet and the bad weather was worsening steadily with cloud

and heavy rain. Just then the crew sighted a well-lit factory

3 miles east of Duren and Gardner decided to attack it

instead of finding Cologne. Twelve 112 pound bombs were

dropped and eleven fell within the factory walls, the twelfth

falling in the road outside. The homeward journey was made

under even worse weather conditions and for two and a half

hours the crew were unable to see the ground at all. They

crossed the trenches at 2,000 feet, under heavy fire from the

ground, and finally landed successfully on Droelandt

aerodrome, despite its small size and the complete absence of

landing lights. By the time they landed the crew had been in

the air for seven and a half hours and had covered some 400

miles, over mainly unknown territory.

From November 1917 until February 1918, very few sorties

were flown because of unfavourable weather and bad airfield

conditions. Squadron Commander Babington was succeeded by

Squadron Commander H A Buss on 1 January 1918 but he too was

posted shortly afterwards and was replaced by Squadron

Commander H Stanley-Adams DSC on 20 February 1918.

Returning from a night attack on 18 February 1918, Flight

Lieutenant E R Barker achieved the rare Bomber distinction of

shooting down an enemy fighter. The attacking aircraft was an

Albatross D5 Scout, a formidable fighter, but Barker's

observer, Flight Sub-Lieutenant F H Hudson calmly waited

until the German Scout was about 20 feet below and 50 feet

ahead of him, having completed its first pass, and then fired

a burst from the front gun into the enemy's front fuselage.

The Scout appeared to stall and, after a second burst,

nose-dived apparently out of control.