207 SQUADRON ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORY

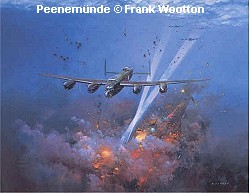

PEENEMÜNDE - AUGUST 1943

by David Balme

written in late 1985 for the first 207 Squadron Association Newsletter

The memorable effort in 1943 was Peenemünde on August 17th. 'Cocky' Cochrane, [AVM The Hon. Ralph A. Cochrane] AOC No.5 Group, laid on a special practice for it - what he called indirect bombing. We had to do a timed run south from Mablethorpe pier, find the wind, and then use it for a new course from a further point to Wainfleet, where we were to bomb on time alone without looking through the bombsight (except that if Lincoln Cathedral should appear in front we were to go round again). Cocky made it into an inter-squadron competition. The winning error turned out to be over 300 yards, but this did not perturb us since we assumed it was to be a method of attacking some large target like Berlin through cloud.

But Cocky blew his top. He visited each squadron in turn, called a mass meeting, and told them that they would be the laughing stock of the Air Force. He reached 207 at the end of a morning, and having torn us apart announced that he would stay for lunch and then take up a Lancaster himself and have a go. Lunch was not pleasant; everyone within earshot was mercilessly quizzed on the latest operational bumf from Group.

Meanwhile, with Chiefy's connivance, we arranged for a suitable aircraft for Cocky, the one that was usually kept for the squadron commander because no one else would fly it: it was one of those that went better sideways than forwards. With it we detailed a crew not famous for subservience. When they got back, Cocky emerged poker-faced, reeled off a list of unserviceabilities, and drove away to harass the next squadron. Wainfleet rang through his result: he had made three runs, with an average error of 38 yards. After that Cocky could do no wrong in our eyes.

When the actual operation was put on, we were amazed to find that the target was not the big city but this tiny research station on the Baltic. Its importance was not explained, but since the bombing height was to be 5000 feet in full moon, and since we were kindly told that if we missed it tonight we would go again every subsequent night regardless of casualties, we got the message. Other groups were to go in first on separate aiming points, while 5 Group had the place of honour - last - and our target was the workshops. To overcome the Peenemünde smoke screen we were to make a timed run down a north-south coast surprisingly like Mablethorpe-Wainfleet, and then the run-in from a second pin-point after finding the wind. Z hour was soon after midnight, so take off was about 2000, still daylight.

There was radio silence as usual, and a green Very summoned us to trundle along the peri track like dinosaurs and queue up until a green Aldis invited us on to the flare path as the previous aircraft began to move: when his tail came up we opened full throttles on the brakes then gently let her go. As always, a little group stands there to see us off; the station commander salutes (the only occasion when a group captain salutes a sergeant first), the WAAFs wave, and off we go with that never forgotten roar. The engineer's left hand supports the pilot's right hand on the throttles; keep her straight, ease her off, wheels up as soon as you think you won't bounce back, flaps in bit by bit, gain speed before height, and now there is half an hour to fly around making as much height as possible before setting course.

From the ground they seem like angry wasps circling aimlessly, until suddenly they all vanish in the same direction; then an anxious wait begins down there, with wondering whether all the equipment was checked, and what the weather will do at the target, and how soon will the German fighters cotton on to our route (there is a diversion on Berlin, hoping to cause them to re-fuel). Over the North Sea we waddle along under full bomb and fuel load, with luck making 20,000 feet at 160 knots indicated. The light fades, but up comes that unloved moon. Near the Danish coast we start letting down, then turn north to find our first pinpoint. A sea mist makes it difficult, and as we fly around we stir up the shore batteries. At 5000 feet now, the light flak seems to spiral lazily towards you and then whizzes past; we tend to prefer the heavy, which can be outwitted, whereas this stuff is hosed up all over the place.

| At last

we are ready for the timed run-in, the navigator has

made his wizardlike calculations, and we suddenly

hear the 'Master of Ceremonies' telling us to avoid

certain target indicators which are falling towards

the sea. Some crew is bombing too early, and he is peeved: "Please remember that I'm down here you stupid prune". Our run is nearly finished, and in a moment we must decide whether to bomb on markers or on time; but now we are in luck, for the bomb-aimer says "Target sighted dead ahead". |

|

So both Cocky and our navigator are vindicated, and finally everything is up to the bomb-aimer and gunners: if they can't get us accurately and safely to the target, the whole enterprise will go up in smoke only too literally.

So here we come, full boost and revs, "...steady, steady - right a bit - steady - bombs going - steady".

Bombing runs are our least favourite moment, and last forever. This time the bomb-aimer is moved to uncharacteristic eloquence: "Cor, look at that" he says. Then "Bombs all away, flash gone off" and a climbing turn west to get the hell out of here. As the bombs left, the aeroplane lifted like a young horse and is now beautifully responsive. A quick glance shows roofless burning buildings below and a runway to the right, but this is no time for sight-seeing: all eyes are watching for fighters, of which there is no shortage. But nothing hits us, though we see other aircraft burning on the ground and one poor devil blows up in the air over there. We climb away to max height, maybe even 30,000 feet where there be lions, and as we get clear out to sea we reach what really the favourite moment. Everything has gone quiet; I look out along the wing where the two port engines crouch like tigers, purring now under reduced boost and revs, but nursing their power if it should be needed; soon the W/Op will bring that disgusting coffee which is pure nectar. But not before he performs one vital task: having had to listen out in silence all night, he is now permitted one call to base; he comes up with information about the airfield state and the barometric pressure there. We set the altimeter for home.

There comes the English coast, dark, dangerous, precious, containing everything that this whole exercise is about. Two searchlights stand like crossed swords, marking an emergency landing strip for those in trouble; but we are not in trouble tonight, touch wood. At base the flare path is already lit up (Hullo Squirrel) and aircraft are plentiful so that we deem it prudent to put on nav lights though we dislike them having regard to intruders. Flying control even want to stack us up to 11,000 feet if you please; what an absurd notion. We all go round the circuit together, and since the people in front look a bit close we make a tight orbit in the funnel, a manoeuvre which displeases the station commander as we later discover.

All safely down, quick chat with the ground crew to tell them how marvellously their aircraft performed, debriefing and pint of alleged cocoa (containing so it is said, bromide for the protection of WAAFs), our operational eggs, sausages, beans and fried bread without which we should unquestionably mutiny, and then to get our heads down. Presently a WAAF orderly comes quietly round the quarters and pulls down the sheet from each sleeping face. Somebody wakes and asks what she is doing "Just checking that my family are all back" she says.

Though 5 Group's total losses are heavy, the nine 207 crews are all back without casualties, and every one of their photographs that can be plotted is on the aiming point - there are so many that Group, penny-wise as ever, stop handing out those Lanc pictures to crews that get aiming points; pity, for it would have been a good souvenir.